A Brief History of Groveland and the Formation of the Groveland Community Services District

We are greatly appreciative to Mr. Mark Thornton, author of A History of Groveland Community Services District, for his exhaustive research. This piece draws heavily from his work, and would not be possible without it. We also owe a debt of gratitude to San Francisco Public Utilities Commission and the Groveland Yosemite Gateway Museum for allowing us access to their extensive photograph collections.

_______________

California achieved statehood in 1850. In February of that year the Governor approved the creation of 27 counties, including the county of Tuolumne. County formation meant the first local governmental services for the mining camps of Big Oak Flat and First and Second Garrote. By 1852, post offices were established in Big Oak Flat and Garrote, and a constable, judge, and tax collector had been appointed. The mining camps were beginning to resemble towns, and miners began to construct permanent structures of wood, stone and adobe. By the mid 1850s the camps were thriving, boasting a population of approximately 1,500 miners.

With the demands of an ever-increasing population, local citizens quickly discovered that the local creeks could not supply the water necessary to support extensive hydraulic mining. In 1855, in response to concerns about the future of mining in the region, a group of concerned miners formed the Golden Rock Water Company. The goal of this newly established organization was to divert water from the South Fork of the Tuolumne River and transport it via open ditch and wooden flume to the Garrotes and Big Oak Flat. The project was quickly underway.

The completed project included forty miles of ditch and a wooden flume measuring 2,200 feet long and 280 feet high. The Flume spanned the valley between Pilot Ridge and Smith Ridge. The Big Gap Flume was now the tallest ever built in the state, and the newly constructed system (costing over $150,000 to complete) delivered its first water to the towns on March 29,1860.

Flat namesake oak. Courtesy of the

Groveland Yosemite Gateway

Museum Foundation.

By the time the project was completed in 1860, Big Oak Flat was a flourishing mining town with 150 commercial and residential buildings and a population approaching 3,000 residents. However, October 24th, 1863 marked the end of Big Oak Flat’s period of prosperity. The town was destroyed, devastated by a fire that some say was visible even from Sonora. Although a few structures did survive the flames, and some were even rebuilt, the town never fully recovered.

By the mid 1860s gold mining was in decline. In July of 1868, to the surprise of no one, the greatly celebrated flume collapsed. Some efforts were made to replace the fallen flume with an inverted siphon. The Golden Rock Ditch remained operational until the mid 1870’s, but the structure was largely ignored for the remainder of the century. The steady decline in gold production and the passage of stricter hydraulic mining regulations effectively brought the placer gold mining industry to a halt. By the 1880s the gold rush was all but over. Big Oak Flat, Garrote, and Deer Flat mining camps had produced an impressive $25,000,000 worth of gold.

Having avoided the fire that destroyed Big Oak Flat, Garrote survived the decline in local gold production much better than its neighbor. First Garrote had always been the smaller, less prosperous neighbor to Big Oak Flat, but had managed to accumulate some three dozen structures around the town’s center. Producing far less gold than the other two camps, Second Garrote grew to only a dozen or so rough dwellings. Around this time President Abraham Lincoln signed the Yosemite Grant which set aside Yosemite Valley and the Mariposa Grove of Giant Sequoias as a state supervised public reserve. In response to these changes, the local economy began for the first time to turn its attention towards farming and tourism. In attempts to make the town seem more hospitable to potential visitors, the merchants of First Garrote agreed to rename it. The citizens decided upon the name Groveland, named for Groveland, Massachusetts, which was the local citizen’s hometown.

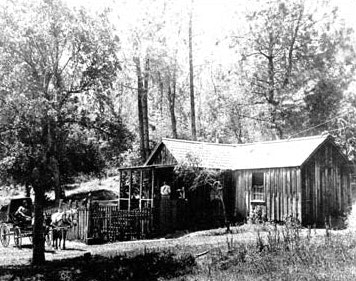

Courtesy of the Groveland Yosemite Gateway Museum.

Although Big Oak Flat and the newly re-named town of Groveland managed to survive the decline in gold production, the local economy was struggling. Fortunately, improvements to deep shaft mining techniques resulted in a hard rock mining boom in the 1890s. This boom brought about a second gold rush to the Mother Lode, and a much needed boost to local economies. From 1890-1900 Tuolumne County experienced an 83% growth rate that affected even such rural outskirts as Big Oak Flat and Groveland. The increased need for goods and services created many new opportunities, and the housing shortage created by the influx of miners produced a boom in local construction business. The gold fever excitement was back and would remain strong well into the twentieth century.

By 1906, as a result of the new deep shaft mining techniques, Groveland and Big Oak Flat had at least three stamp mills in operation, averaging twenty stamps each. One such stamp mill, owned and operated by the Rhode Island Quartz Mine, was located on GCSD property between modern day Mary Laveroni Community Park and the Groveland Community Services Administration building.

note that the dirt road through town became a quagmire every winter. F.R. Stanley Collection, courtesy of the Groveland Yosemite Gateway Museum Collection.

The new century was also witness to the construction of a mile-long mining railroad in the Big Oak Flat Basin and the birth of hydroelectric power. Pacific Gas and Electric (PG&E) power arrived in Big Oak Flat via the Parrington Distribution Company. Although Fred Parrington, superintendent of the Longfellow Mine, was chiefly concerned with providing power to his mine, the line extension from Jamestown to Big Oak Flat would benefit the entire community. By 1909 the power lines had been extended to Groveland, and for the first time the town had electric lights.

Water was still, as always, a chief concern for the inhabitants on the hill. Several power companies were busy exploring the high country, filing claims on every available hydroelectric site, and seizing water rights wherever possible. It was around this time that the Big Creek Mining Company purchased, and attempted to revive, the long deserted Golden Rock Ditch. Since the collapse of the Big Gap Flume in 1868, area residents had relied on individual wells and springs for all their personal water needs. These hand-dug wells rarely exceeded twenty feet in depth, and though somewhat unreliable, were generally adequate for the lifestyle of the time.

Though there was not yet any organized effort within the community to create a water delivery system, in 1908 the Cassarretto and DeFerrari families did unite to create a system of interconnected wells to service various family properties. This small in-town system was eventually abandoned, as were efforts to revive the Golden Rock Ditch. Though many entrepreneurs purchased the rights to the ditch with grand visions of restoration and profit, none realized that dream. The Yosemite Power Company purchased the rights to the ditch in 1910, but in less than a decade had abandoned the ditch west of Hamilton Station (later Buck Meadows).

After experiencing several years of financial losses, the Tuolumne Electric Company folded also. Groveland was again without power, and the hard rock mining boom was all but over. Gold prices had dropped significantly, and in response to the foundering gold market and the onset of World War I many gold mines suspended production.

The City of San Francisco had long anticipated that local water supplies would be inadequate to meet the demands of their growing population. After turning their focus to the Sierra Nevada Mountains in search of a sufficient water supply, the City purchased the rights to Hetch Hetchy Valley and Lake Eleanor in 1901. Much controversy surrounded the City’s plan to flood the valley, but the earthquake of 1906 dramatically and painfully demonstrated the inadequacy of the City’s water system. So in 1913, with this disaster still fresh in the minds of many, Congress finally passed the Raker Act granting approval for the flooding of the Hetch Hetchy Valley.

Construction on the Hetch Hetchy system began in 1914, and the economic slow down in Groveland and Big Oak Flat soon subsided. Besides construction of the dam and pipeline, a railroad was required. Groveland was selected to be the site of the railroad shops and roundhouse, and would also serve as the “Mountain Division” construction headquarters. Over the next several years, laborers, engineers, contractors and a multitude of other workers inundated the two towns. Homes left vacant by earlier miners were now at a premium, and rental cottages were being hastily built.

Not only did the City of San Francisco bring the railroad industry to the hilltop communities, but they set out to construct many new buildings in the Groveland town site. In addition to the construction of a hospital, the city maintained an ambulance service (rail vehicle), postal service, and passenger and freighting services. A small powerhouse at Early Intake generated electricity with water from Lake Eleanor, finally providing Groveland full electricity in 1918. To ensure adequate water supply for both fire protection and use at their Groveland facilities, the City leased the Golden Rock Ditch. Once again Groveland and Big Oak Flat had access to the water that flowed from the Tuolumne river. Fire hydrants and hose reels were installed, and a small in-town water system was constructed. In order to provide communication between its construction camps, offices, and railroad stations, the City also installed an expansive telephone system.

The townspeople embraced these new changes, and many considered the Hetch Hetchy years to be a Golden Era. The town’s population swelled to 250 people, a number which more than doubled with the arrival of the Hetch Hetchy construction crews. The wealth and prosperity prompted many changes within the community. The locals instituted a baseball league, the community approved funds for a new school house, and in 1920 the Big Oak Flat Road was finally paved.

For all of this progress, one community service was still sorely lacking in Groveland: that of a sewage collection and disposal system. While most local residents had constructed outhouses to fulfill their needs, almost all of the boarding houses (hotels) and restaurants in town catering to this new population of construction workers kept septic tanks with overflow hoses feeding raw sewage directly into Garrote Creek. After several inspections from state officials, Hetch Hetchy was eventually forced to install concrete holding tanks for their excess sewage. But complaints from downstream ranchers reveal that most businesses continued to dispose of their waste and sewage into the creek. The problem would not be properly addressed in Groveland for some time.

schoolhouse, 1913. This building now

houses Yosemite Bank. F.R. Stanley Collection. Courtesy of the Groveland Yosemite Gateway Collection.

The O’Shaughnessy Dam was dedicated in 1923. In 1925, the construction headquarters were moved from Groveland to Hetch Hetchy Junction, bringing to a close the prosperous Hetch Hetchy era. The Raker Act required the City to dismantle facilities associated with construction activities upon completion of the project, and by 1930 few of the original construction facilities remained intact. Also gone were many of the services that the community had grown accustomed to.

Unfortunately, circumstances were to worsen before they improved. The 1930s ushered in the largest economic depression in modern history. Thirteen million Americans were now unemployed, approximately 11,000 of the country's 25,000 banks had failed, new home construction fell by 80%, and the income of the average family was reduced by 40%. Groveland and Big Oak Flat were not immune to this economic hardship. Local tourism, ranching, and mining were all affected by the dire state of the economy. The gold mining industry declined to such an extent that most of the area’s stamp mills were either dismantled or sold for scrap. Many, if not all, hydroelectric endeavors on the Middle and South Forks of the Tuolumne River were postponed indefinitely, and the recent completion of Hetch Hetchy meant the absence of much needed construction dollars in the local economy.

Gateway Collection.

By the summer of 1935, after 7 years of below average rainfall, springs and wells in Groveland and Big Oak Flat began to dry up. Concern was growing, and local resident George Laveroni attempted to convince his neighbors to consider tapping into the Hetch Hetchy aqueduct. It seemed that San Francisco was willing to allow the townspeople access to the water in the aqueduct, if they would agree to purchase the existing water line from Second Garrote to Groveland. After taking into consideration the purchase cost ($3,000), the cost of maintaining the line, and the cost of the water itself, the townspeople determined that the cost was too high for the struggling community.

Although Groveland had passed on an opportunity to secure a reliable water source from Hetch Hetchy, they could no longer ignore their sewer and septic problems. In 1943, the County Health Department got involved. It seems that local rancher John B. De Martini had lodged a formal complaint with the Tuolumne County Health Inspector regarding the dumping of raw sewage into Garotte Creek. Mr. De Martini used Garrote creek to irrigate his alfalfa fields, and had been voicing concern over its pollution since the 1920s. For years he had urged the townspeople to maintain the Hetch Hetchy installed sewer system downtown, but to no avail. After an inspection, the County Health Inspector sent notice to all users of the sewer system that “conditions must be corrected.” After a public meeting and some discussion with the District Attorney, citizens decided that a petition would be circulated for the formation of a Groveland Sanitation District. Fifty-one registered voters from the town site signed the petition. After a public hearing, the County Board of Supervisors passed a resolution establishing the “Groveland Sanitation District” on June 26, 1944.

Thomas Reid, Joseph Cassarretto and Frank Ferretti were appointed as the advisory committee to the newly formed District, whose service area was to coincide with the boundaries of the town site of Groveland. The District eventually became known as the Groveland Sewerage and Water District, and struggled throughout the 1940s to meet its responsibilities to the community. However, good times were just around the corner. Groveland was rebounding nicely from the depression, helped immensely by the post-war boom and the renewed interest in the Mother Lode as a tourist destination. Local hotels and restaurants welcomed weary travelers on their way to Yosemite, and in 1952 the Big Oak Flat Road was renamed Highway 120.

That same year members of the community, still plagued by inadequate wells and springs, were approached by local resident and County Supervisor Millard C. Merrell regarding the formation of a community services district. In 1953, with help from many local businessmen, including Erwin Vassar, Joseph Cassaretto, George Laveroni, T. Wesley Osborne and Berger Williamson, a petition for formation was circulated throughout the town. The petition was successful and on April 22, 1953, the Tuolumne County Board of Supervisors established the Groveland Community Services District and scheduled an election. On June 9, 1953 the community overwhelmingly approved the formation by a vote of 52 to 7, and elected 5 Directors to serve on the Board. The first Directors would be Mary Laveroni, Joe Brunette, Birger Williamson, Rose M. Hanson, and William H. Rowley. On August 19, 1953, the Groveland Community Services District was officially established as a special District.

As with the Groveland Sewerage and Water District, the District’s boundaries coincided with those of the town site. However, the District was authorized for much more than the collection and distribution water and wastewater. The District was given the authority to provide fire protection, public recreation, street lighting and garbage collection. Although authorized, the District did not pursue all of these functions. The Directors did however reserve the right to undertake any new function deemed necessary and fiscally viable.

During this period Groveland enjoyed the highest level of wild land fire protection it had ever known. From the devastation of the Great Depression had come several immensely successful federal programs, which in turn had established an infrastructure for wild land fire protection that greatly benefited rural communities. Grovelanders were protected by both Stanislaus National Forest and Yosemite National Park stations, and Tuolumne County had even agreed to station a full-time engine in town. With the formation of the District, the community now benefited from the presence of a full-time fire chief, ten volunteer firemen, and a newly installed siren on top of the local grocery store. Eventually the District took responsibility for the maintenance of the County-owned fire engine, and determined to annex the community of Big Oak Flat into the fire district.

Not long after the formation of the District, the Board submitted a formal request to the City and County of San Francisco for access to the Hetch Hetchy water system. Unfortunately, when it was discovered that approximately $80,000.00 would be needed to install the necessary water system from Second Garrote (access to Mountain Tunnel) to downtown Groveland the project was quickly dismissed. The District continued to rely on a series of local wells for its water supply, and struggled to maintain its systems. The success of the District during these early years is undoubtedly attributed to the determination and limitless generosity of many local residents. Many residents donated not only their time and services, but personally supported the maintenance of the District’s water and sewer lines through cash donations.

Over the next several years, residents of the community became increasingly concerned over both the quality and the sustainability of the current water supply. After several directors voiced similar concerns, arguing that Hetch Hetchy water was the only viable solution to these problems, communication began again between the two agencies. On or about 1960-61, the Groveland Community Services District approached the City and County of San Francisco as to the possibility of purchasing Hetch Hetchy water. Hetch Hetchy Water and Power officials confirmed the availability of water, but it would be up to the District to find funding for the necessary system infrastructure. In 1964 Groveland residents voted overwhelmingly to accept a thirty-year, low-interest construction loan from the State of California under the Davis-Grunsky Act. The loan marked a turning point in the history of the District, as it would fund the improvements necessary to obtain water from Hetch Hetchy and supply Groveland with an abundant and pristine water source.

In the following years, the Community Services District approved its first contract with the City and County of San Francisco and installed both a pipeline from the water source at Second Garrote and a 500,000 gallon steel water storage tank in Groveland. The District gained access to the water through a 500 foot-deep air shaft which dropped into the Hetch Hetch Mountain Tunnel beneath the Second Garrote Basin. The air shaft had at one time provided Hetch Hetchy workers elevator access to the Mountain Tunnel during its construction. The new tank was installed west of this access point, at the edge of town near what is now Tenaya Elementary School.

These changes were accompanied by a sizable expansion of the District’s service area. The District expanded to incorporate areas both east and north of the town site, and completed the long-anticipated annexation of the community of Big Oak Flat. The District was a success, and for the first time Grovelanders had a clean and plentiful water supply.

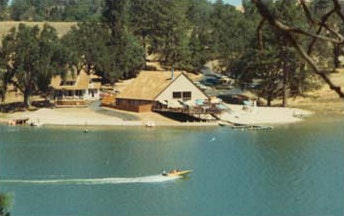

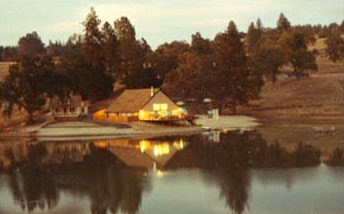

Subsequent years brought many changes to the once tiny community, not least of which was the development of the Pine Mountain Lake residential subdivision and the construction of the sprawling 202-acre recreational lake by the same name. These changes meant rapid growth for the modest Groveland water and sewer systems. New water distribution and wastewater collection systems were extended northeast of the town into the Boise-Cascade developed Pine Mountain Lake subdivision, and west to meet the needs of the recently annexed community of Big Oak Flat.

When lots in the Pine Mountain Lake subdivision went on the market in 1969, real estate agents from Boise Cascade commenced a vigorous media campaign promoting Groveland as “the ultimate mountain getaway” and prospective buyers flooded to the foothills. Although the subdivision held the promise of increased business for the small community, many locals observed the transformation with an air of nostalgia or even resentment. In addition to the 4,000 home sites, Pine Mountain Lake offered a private lake, marina, clubhouse, 18-hole golf course, tennis courts, swimming pool, children’s playgrounds, stables, camping and picnic areas, and airport. Boise Cascade transformed the once abandoned schoolhouse and the rundown Groveland Hotel into modern office buildings. The developers also supervised a number of aesthetic renovations to the downtown area. Long abandoned businesses began reopening their doors to crowds of eager tourists, and “no vacancy” signs were once again commonplace along Main Street.

Over the next thirty years the District continued to expand its service to the community. Although many locals were hesitant to accept the changes brought about by the development of the new subdivision, it became clear that the Pine Mountain Lake subdivision could breathe new life into the Groveland economy. The construction of new homes in Pine Mountain Lake created much needed work for many local contractors and craftsman, and fostered the development of downtown businesses. As the population of Groveland continued to grow, so did the District’s infrastructure.

Today, the Groveland Community Services District provides pristine Hetch Hetchy water to over 3,000 homes in the Groveland/Big Oak Flat community. The District maintains over 70 miles of water mains, five water tanks, two full-time and one emergency water treatment plant. The District’s wastewater treatment plant and 35 miles of sewer collection pipes also serves over 1,400 homes in the Groveland/Big Oak Flat community.

In addition to providing water distribution and wastewater collection services, the District also provides exemplary fire protection service through the Groveland Fire Department and manages a number of community parks, including Mary Laveroni Community Park and Leon Rose Ball field.